CHAPTER 4

The Rocky Mountain Irrigation System

photo: elbertprepp.com

Dorp

and Sam traveled north by east. A breeze pushed them up to the

Rockies near Colorado Springs.

About three in the afternoon, they

went over the continental divide. Sam asked Dorp what was going to

happen next.

“Up

to now, Sam, you’ve seen water in nature. Soon, you’ll see water,

nature and humans working together. We’re nearing a water-powered

electrical plant AND a multi-state irrigation system. Both

irrigation and power generation start with the snow on this

mountain, Mount Elbert, the highest peak in Colorado. At high

altitudes, snow begins to accumulate while you’re still sweating,

playing baseball on Labor Day. That same snow may not completely melt

until the next 4th of July.”

“This

is a big Mountain. I have a joke. Why don’t mountains get cold? “

“I

don’t know, Sam. Why don’t mountains get cold?”

“Because

they wear their snowcaps. Hey! Look at all the big rocks sitting

loose on top of this mountain.

Some are bigger than my dad. I didn’t

know that mountains had loose rocks on them.”

Dorp

spoke like a tour guide: “They do on level spots like this. Quite a

sight, no? This mountain is a

14er, as mountain aficionados would say. That means it’s at least

14,000 feet tall. Mt. Elbert is in the state of Colorado, which was

once part of the Louisiana Purchase, bought from France in 1803. Mt.

Elbert was the biggest mountain that America owned at the time,

though the native inhabitants had known about it for a long time. The

snowmelt that comes down the east side of Mt. Elbert in the spring becomes a part of the Arkansas River. It’s about to rain.

Let’s see where that puts us.”

“Whoa

cowboy,” Sam interrupted, “Why is a river in Colorado called the

Arkansas River?”

“Sam,

the Arkansas River was first spotted by white men where it empties

into the Mississippi River. That is in what is now the state of

Arkansas. The name ‘Arkansas’ has to do with a native tribe that

lived near the river where the white man first saw it. So, they named

it the Arkansas River. The Arkansas River actually begins here near

Leadville, Colorado and empties into the Mississippi River, about

1,500 river-miles away.

Sam

was confused, “Wait! You said the Arkansas River flows from

Colorado, which is west to East. I thought rivers flowed from north

to south. What gives?”

“Generally

speaking, yes, water flows toward the equator. In the northern

hemisphere, that means north to south. But water flows downhill,

no matter what direction ‘downhill’ happens to be, Sam. In this

case, it can be from west to east too.

Okay

Sam: time to get wet, so to speak. We’re going into the river and

go downstream to see if we can become irrigation water. This will be

like a ride in the water park for you. That is, if we’re not pulled

into the underflow.”

“What

is ‘underflow?”

Dorp

explained: “All moving waters lose part of their water into the

ground they flow over. If they flow over rocks or concrete, the loss

is minimal, into the cracks. If the water flows over ground with a

clay in the soil, the ground can become saturated and seal up pretty

well. However, in arid areas, where the water is needed most, the

ground is often very sandy, which makes it porous like the beach. It

drinks up a lot of water.

“Where

does the water go, Mr. Dorp? “

“Down;

it percolates into the water table.”

“Is

that like an aquifer?”

“It

can be, Sam, depending on its size. Every aquifer is a water table,

but not every water table is an aquifer.

A water table is a warehouse

of water hidden underground.”

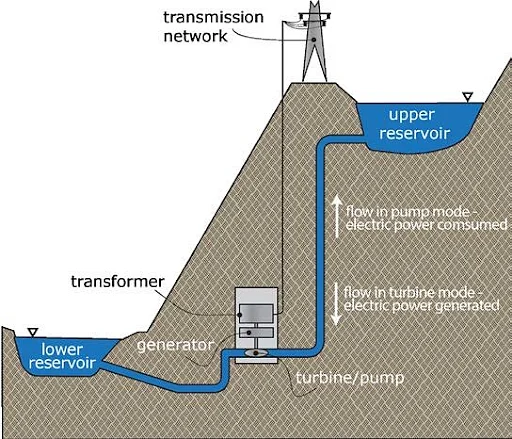

The

vapors over the mountain condensed and Sam and Dorp became rain. They

dropped into Mt. Elbert Forebay,

a manmade catchment

(artificial lake) built to

hold water for the Mt. Elbert Power Plant. The water is discharged

from the Forebay down to the powerhouse where two Francis

turbines turn electrical

generators that create 100 Mega-watts of electricity each. These

turbines are machines that create electricity from water. A different

kind of turbine takes power from a jet engine and turns it into air

power and makes planes fly.

In the 1840s, A Massachusetts lock and

canal engineer named James Francis refined a couple of turbine

designs from the 1820s and made the water turbine 90% efficient. (You

thought the turbine was a modern machine, didn’t you?) The turbines

of that time turned river currents into mechanical power to grind

grain and cut lumber. Dorp

and Sam rode the water slide from the Forebay through one of the

turbines and helped spin it around. Then they sat there until dark and were pumped by the same turbines back up into the catchment.

“What

is going on here? Sam asked. If were supposed to be generating

electricity, we just wasted a lot of electricity getting pumped

uphill back into the same lake we came out of, didn’t we?”

Sam

didn’t understand the economics of 'timed power generation'. During

daylight hours, when Sam and Dorp first turned the turbine to make

electricity, the power company sold that electricity for a certain

price. Electricity is cheaper at nights, because many factories and

businesses are closed. During the night, this power station buys

cheaper power from the grid to pump that same water back up into the

catchment so it can turn the turbine again and make more electricity

that will be sold for a higher price during daylight hours, when

businesses and factories use lots of electricity. The people that run

this power station know that their water supply is limited to snow

melt. So they reuse it. They recycle water to make electricity.

Pretty clever, no? Yes!

But then Sam voiced a thought, "What happens when a lot of electric cars need to charge their batteries at night?

Won't that raise electric fees for everyone, and make places like this out-of-date?"

"We will have to wait and see, Sam."

After

a few trips up and down ‘the turbine trail’, Dorp and Sam were

pushed into Twin Lake, and then into the Arkansas River nearby. While

they were traveling down the river, they saw solar heat and wind pick

up other molecules of water from the river and become airborne.

About

100 miles to the southeast of the power plant on the Arkansas River

is a town called Canon City, Colorado. The ten miles of the river

upstream of Canon City (pronounced 'Canyon City') is a stretch of river called the

Royal Gorge. Sam and Dorp

made it to the Royal Gorge and were being churned around when they

hit a large rock in the stream and were splashed onto the bow of a

river raft filled with weekend-adventurers. That stretch of river is

a magnet for tourism.

“Wow!”

Sam said. “Now I know what it’s like being in a washing machine.”

“Yes,

I’ve had a few trips through washing machines, and usually find it quite agitating,” Dorp deadpanned.

“Why

is the water so rough here, Mr. Dorp??”

“Gravity,

a narrow riverbed, and big rocks make for the kind of ride we have

on this stretch of the river.

The first reason is gravity.

Water is a liquid, it tries to stay as low as it can, so it presses

tightly to the bottom of the river. The Arkansas River drops over 300

feet in the ten-mile-long strip in the Royal Gorge, so the water is

busy trying to stay low.

Second, remember the big rocks on Mt. Elbert? There are also big rocks in the Arkansas Riverbed that

the water has to flow past.

Third, the high sides of the

gorge make a narrow path for the water. The narrower the

channel, the faster water flows."

"Look up Sam, see the bridge coming up above us? That is the Royal Gorge Bridge that so many people come to see.

You get to see it from the river."

Suddenly,

the raft nosed-dived into the water and sprayed everyone on board and sent Sam and Dorp back into the river. They went downstream. The

river calmed down near Canon City, because the river widened out

there, making for a gentler, slower ride. They

traveled down the river for many, many miles.

After a few days, they

neared Garden City, Kansas. They were pulled out of the river by a

diversion weir

and sent down an irrigation intake, a water off-ramp in the river. They parted ways with the

Arkansas River.

A

diversion weir is a low obstruction across a river or stream that

raises the level on the river slightly at that point. This allows

water to be diverted into a canal or channel to irrigate fields.

They

went into a deep, wide canal. As they moved down the canal, there

were ‘head gates’ that diverted the ‘ditch water’ as it is

called, into smaller canals that fed directly into nearby farms, or

into secondary feeder ditches that might travel for miles before

reaching the proper field.

Both were quiet for a while, then Sam spoke “I’ve been thinking;

plants need water, and I guess the farmers have to pay for this

water. How do they know how much water they need?”

“Good

question, Sam. Each type of crop needs a certain amount of water at

each phase in its life. The amount of water each crop needs also varies

according to soil type, amount of wind and the sunlight the plant gets. These

calculations are called 'transevaporation rates'. This is how much

water transpires out of a plant as it grows, plus how much water

evaporates out of the soil during the growing season. Even the type

of irrigation affects the amount of water needed, because some

methods of irrigation are more efficient than others.

Dirt ditches

lose more water to seepage than concrete ditches, for example.

Scientists and farmers alike have been studying this topic for

decades and have mathematical formulas to determine how much water is

needed for each field.

Long

story short, it is calculated in acre-feet.”

“What

is acre-feet, Mr. Dorp? I didn’t know land could walk.”

“Bad

Joke, Sam. I have a farm joke for you. How do dairy farmers count

their herds? With a COWculator.

And how do they know which day it is?

With a COWlendar.

Anyway, the US uses the acre

as a way of measuring land. An acre is 43,560 square feet, about the

size of a football field, without the end zones. Imagine a football

field covered with water, one foot deep. That would be 1 acre-foot of

water, which is 325,861 gallons of water.”

“Those

are terrible jokes, and that would also be one very wet football

field,” said Sam.

“Can you imagine playing football in a field

with a foot of water in it? Wow.”

“While

it may seem like a lot of water, Sam, absorb this: Each acre of corn

in around Kearney, Nebraska needs a little over 2 acre-feet of water

to make a crop, whereas alfalfa in parts of California can

require over 4 acre-feet of water to grow.

This shows the need for

accurate formulas and calculations, especially since about 15% of US

croplands are irrigated.”

“Then

why do they grow alfalfa instead of corn, if corn takes less water?”

“This

has to do with the soil type and other factors. Alfalfa doesn’t

need to be replanted every year, and it is used to feed milk cows. California has a lot of cows. and need hay. Here we go, we’re going to be

diverted through another headgate. Let’s see if this is where we go

to work or if this is a long-distance supply canal.”

They

slipped though the headgate as easily as chocolate milk though a

boy’s straw. Dorp went on to explain more about irrigation. First,

there are two sources for the water; surface water brought in by a

ditch company, or underground water pumped out of an aquifer.

Irrigation methods include surface

irrigation, as water is

applied directly to the surface of the dirt, either by flooding

the area, like an alfalfa field, or row

irrigation, where water is

sent down prepared trenches between the row crops. The second major

type is sprinkler irrigation, accomplished though overhead

sprinklers, which are fed with underground or reservoir water,

brought from an irrigation canal. The very last type is

micro-irrigation,

which uses tubing laid either on the surface or underground to water

the plants.

“Which

type of irrigation is the best?” Sam asked.

“That

depends on what types of crops the farmer is raising, the source of

the water, and how much money the farmer has.

Some systems require

less labor to operate but are very expensive to buy in the

beginning. Irrigating with siphon tubes is a lot of work, but it’s

less expensive than a pivot sprinkler system.”

Dorp

and Sam then hit a head gate and were put in field ditch at the upper

end of a corn field. They were going to irrigate corn; or so they

thought. As they poured down the ditch with hooptillions of other

dorps (hooptillions is my word), they saw that the farmer had set a

temporary dam made of plastic tarping attached to a metal pole. The

pole lay across the top of the ditch and the tarp hung down and was

secured at the bottom with a few shovels of dirt. As the water filled

the ditch behind the plastic dam, the farmer began ‘setting the

tubes’. The tubes, nearly as long as the farmer was tall, were

already laid out in a row for the so the farmer could prime them

quickly.

As

the ditch filled behind the dam, the farmer put the long side of the

double-bend siphon tube in the ditch water and made special moves

with his hands to get the water to come out the other end of the

tube. He then quickly laid that end of the tube in the row lower than

the level of the ditch water. Gravity kept the water flowing through

the field, between the rows of corn. The lower the siphon tube was

from the level of the ditch water, the faster the water flowed.

The

more tubes used, the lower the water in the ditch flowed, which meant

less water flowed through each tube. The tubes had to be adjusted so

the water flow would balance amongst the rows. After all the tubes

were set, it took a couple of trips down the head of the field to get

the flow ‘just right.’

Sam

and Dorp sat in the final supply ditch for a while, then were sucked

up through one of the first tubes he set, close to the temporary dam.

The ride through the tube was like being at a water park.

“Sam,

we’re flowing down the field now. It looks like we’re going to

make it to the end the row. Let’s see if we are absorbed by

the corn or evaporate into the air.

Either way, we’re off on a new adventure.”

The

adventure was more than they imagined. While they were sitting in a

little pool of water at the end of the row, a barn swallow swooped

down for a drink and took Sam and Dorp off with her.

“Well.

I wonder where this will lead us. But, not to worry Sam. Even if we

go clear through the bird, it takes far less time to go through a

bird than through a horse.”

“That’s

small consolation,” Sam moaned. “I guess I’m destined to be

bird poop on someone’s windshield.”

They

slid down the bird’s throat, and past a sack in the bird’s

throat. Sam asked what that sack in the throat was.

Dorp

explained, “That’s the bird’s crop.

It is a storage sack in the throat. Small birds may be eaten by other

creatures.

These weaker birds usually eat seeds and insects. A seed

bird can fly into a dangerous area and gather more food than it can

digest right away. This food goes into the bird’s crop. The bird

flies back to safety, where its crop will gradually push the food

into the stomach where it will be digested. The first chamber in the

stomach is called the proventriculus.

It is the chamber where acid is released and food is broken down.

The

second part of the stomach is called the ventriculus,

or gizzard, as it is commonly called.”

“Oh,

so the grain crop goes into the bird’s crop? HA! Wait…Oh! I

love fried chicken gizzards,” Sam gushed. Grandma Tessie makes

them whenever I visit. She batters and fries them like regular

chicken. Even dad asks for them now when we visit.”

“The

gizzard is a very specialized piece of biology. The bird ingests

grit, sand, or small pebbles and they go into the gizzard. Then when

the bird eats seeds, grains, or even hard-shelled bugs, which are

tough to digest, the gizzard acts like a grinding mill and pulverizes

the seeds and grains so the intestines can absorb nutrients from

them.”

Dorp

and Sam made their way through the barn swallow’s digestive tract,

and found themselves not on a windshield, but deposited in a nearby wheat

field, where a light rain washed them into the sandy soil and they

were absorbed by the wheat plant. They became part of the wheat crop, which

holds 10-15% moisture.

This

happened a week before harvest time. They were harvested by a huge

combine, hauled to the mill, milled into flour, bagged and sold to a

grocery distributor. Dorp and Sam wound up in a grocery store in

Guymon, Oklahoma.

dorpwet.com

CHAPTER 4

siphon tube irrigation system

Photo: Old Iron - tractor magazine