CHAPTER 2

Dandelions and Horses

Dorp and Sam began working their way up

the dandelion, like water climbing a straw. Sam watched as the cells

of the plant which had been slack and deflated, get plump and rigid,

like his bicycle tire when he put in air.

Sam

asked Dorp, “How does the plant put water in its cells without the

water gooshing back out when they get full?”

“Well

Sam, plants have a special way to intake and retain water. This

process of plants taking on water through the roots is called

osmosis.

Once in the root, the water moves up the stem of the plant via

capillary action.

Then the tiny pores on the leaves open up and the leaves begin to

lose water. This is called transpiration,

when water evaporates from the leaf of the plant. There

is a lot more to learn about this, but I would have to use words like

xylem, hydraulic conductivity, apoplastic barriers, and the like.

For right now, just understand that roots drink water through osmosis

and the leaves lose water through transpiration, OK?”

“Hmmm,”

Sam pondered, “So transpiration is when plants sweat, huh? I guess

we are about to be sweated out of this dandelion. Oh. Look at the

rabbit. What do you call 10 rabbits hopping backwards together?”

“I

don’t know, Sam.”

“A

receding hare-line. Ha!”

Dorp

ignored the joke, “After a fashion, plants sweat. So far, you’ve

heard four terms of water movement: precipitation,

percolation, osmosis, and transpiration.

We dropped to the earth via precipitation, trickled down into the

ground through percolation. We were absorbed into the roots by

osmosis, and we move out of the plant via transpiration. Plant

material, called cellulose, has a certain water level it tries to

maintain, whether the plant is alive or dead. Even a dead plant will

absorb water when it rains. Its cells try to stay damp, like your

mom’s kitchen sponge. When it absorbs all the water it can, it’s

called the saturation point.”

“So,

plants have cellulose, hmmm? My mom says she has too much cellulose

on her thighs."

Dorp

corrected Sam: “I think she meant cellulite, not cellulose.”

“Mr.

Dorp, she sat on my lap once, and there is nothing light about it.

Oh. And now we move to the end of the leaf and are transpired, eh?”

“Yes,

if that horse doesn’t eat us first.”

Sam

looked up and saw the horse grazing, moving closer and closer, like

an eating machine moving side to side. He had seen horses before, but

not from this angle.

“Mr.

Dorp! I don’t want to get chewed up.”

“You

are water,” Dorp explained, “Water doesn’t get chewed.”

Sam

was not comforted by this news:

“But

I don’t want to be eaten! I don’t want to go inside of a horse.”

“You

are now water. You have no control. This is what we do.”

Sam

couldn’t understand how Dorp could be so calm all the time. He was

like a combination of President Coolidge and his Uncle Steve. Suddenly,

it got dark. Sam heard a crunching sound. He felt himself being

lifted into the air as the horse raised his head to swallow the

dandelion. Sam felt himself getting even wetter. He complained to

Dorp that the water felt slimy.

Dorp

spoke: “You are feeling the horse’s saliva. Horses produce up to

10 gallons of saliva a day, and it is 99.5% water.”

“Horses

make 10 gallons of spit a day?”

“No

Sam, unlike camels, horses don’t spit. Since horses eat vegetation,

they need saliva to moisturize the ingesta

as it is called. They mostly

eat grass, hay and grains. Digestion begins in their foregut.”

“What

is a foregut?” Sam asked.

Sam was already getting tired of this

learning on what was supposed to be summer vacation. Maybe the school

librarian would give him extra credit on the summer reading program.

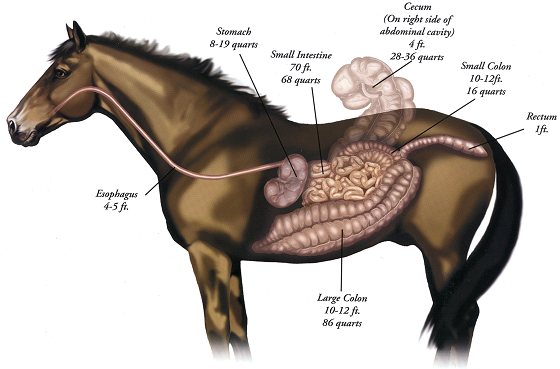

“Horses

have a two-part digestive tract. The foregut is the forward half of

the horse’s digestive tract. This is the stomach and the small

intestine. The front half does the easy stuff and the simple foods

are absorbed in the front small intestine, and the tough stuff passes

through the cecum, to the hindgut, which is the large colon, then the other small colon. You humans don’t have one of those.”

“Really?

Two digestive tracts in one animal? Sometimes I think little Abby has

two digestive tracts the way she goes through diapers. So is that why

horses are so long? “

“Perhaps

so, Sam. Grazing animals like horses need a lot more water than other animals to digest their

food.

If they are not given enough water to keep the food moist as it

passes through them, they may flounder or get colic.

This is especially true when they eat aged hay, which has lower water

content than green grass.

Older horses have it the worst in the

winter. When they are eating the drier hay in winter, their drinking

water will also be colder, and older horses have sensitive teeth that

don’t like cold water. They may dehydrate, and not be able to

digest the hay, and they can get very sick. Older horses need warm

water in cold weather.

Anyway, get ready for a slow ride.”

“How

could we be put to work in a horse?” Sam wondered out loud.

Dorp

answered, “In much the same way as in your human body. We are being

eaten; no doubt about that. When we reach the intestines, we will

either stay with the raw food mass, to act as a conditioner and

lubricant, or we could be absorbed by the intestine and help hydrate

the body. We may wind up as saliva and actually go through the

foregut of the horse twice.

I was once saliva in the same gazelle

three times before being turned into ear wax. We might become blood;

we might be water in muscle or organ cells. Eventually then, we would

be recycled out of body through the end of the digestive tract or the

urinary tract. We could also leave the body as sweat or tears or be exhaled as vapor out of the lungs.”

“There

are a lot of jobs for water in a horse, “Sam said thoughtfully. “I

would prefer to leave as breath vapor.

That sounds a lot less icky.

“Wishful

thinking, Sam. Water molecules have no choice of where we go or what

job we do.”

Sam

could tell they were deep inside the horse. Time in the stomach went

slow but he and Dorp talked a lot.

“I

wish I could see what is going on now.” Sam said, being squished

and rolled around in the horse’s stomach.

“Very

well; you now have night-vision.”

Sam

looked around and thought that the inside of a horse’s stomach does

not look particularly cool. It was cluttered and drippy and oozy and

moving all the time. It looked kind of like his room, except his room

wasn’t this wet and his walls didn’t move. He was glad he didn’t

have a sense of taste or smell right then.

Sam

asked, “Why don’t I get hungry? I should be hungry by now.”

“You

are water, Dorp replied. “You have no nutritional needs, so you

have no stomach; therefore, you cannot feel hunger.”

Sam

sighed. “What a happy life water has. Wait; I have a joke. Why do

cowboys ride their horses?”

“I

don’t know, Sam. Why do cowboys ride their horses?”

“Because

horses are too heavy to carry.”

“Sam,

we’re moving through the digestive track, past the small intestine.

We now have a 50/50 chance of becoming manure.”

“Oh

great! That’s exactly how I wanted to spend my summer; being a pile

of horse poop! This is not my idea of high adventure, you know?”

“Really,

Sam? Since you’ve left home, you’ve of become a molecule of

water, slid down the side of an airplane traveling over 500 miles per

hour; fallen over five miles without a parachute. You’ve been

sucked up into a dandelion; then eaten by a horse and have seen more

about horse digestion than the average veterinarian; and already

you’re bored?”

Sam

defended himself, “I didn’t say I was bored. I just can’t make any

decisions for myself anymore. I didn’t realize how many choices I

could make when I was a boy. I thought everyone else controlled my

life. Wow, water has no say in anything.”

“You’re

right, Sam. You don’t have control on a roller coaster either, but

you decide to enjoy the ride. We’re passing through the large colon

now. We have been absorbed into a bit of indigestible hay stalk, so I

suspect we are going to pass through the horse without being

absorbed.”

“Did

you know all along we were going to be pooped out and you didn’t

tell me? Really?”

“Sam,

first of all, I didn’t know exactly where we were going to go,

though I did tell you that a horse produces 10 gallon of saliva a day

and doesn’t spit. Figure that one out, Galileo. Besides, you don’t

seem to do too well when you know what is going to happen before

hand, so I’ve decided to let you be surprised. You’ve survived

everything but stagnation.

You’ll be fine. Just relax and enjoy the

trip.”

“Sure...

Enjoy being horse poop. Oh, I can see the first week of seventh

grade. The English teacher will have us write a report on how we

spent our summer vacations. My report will say that I spent the

better part of the summer in a pile of decomposing horse manure in a

pasture in western Nevada.

To which, Miss Miflin will glibly say to

me, ‘You know Sam, I think it’s time you met Mr. West; the new school

principal.’”

“Sam,

Dorp sighed, “You will spend your summer with your family, and as

their boy. You will not have to spend your summer vacation in a pile

of manure.”

“Thank

you, Mr. Dorp. Oh no! I think I see the light at the end of the

tunnel, as dad would say.”

“That

is a cleverly turned phrase, Sam. Shakespeare would say, ‘what

light through yonder window breaks.’

Next stop: the pasture.”

I

won’t detail this step of Sam’s journey, but you can guess. They

left the digestive track and piled up on the ground.

Very often,

where there is dung, there will be yellow

dung flies. That evening,

yellow dung flies descended on the pile to mate and the females laid

eggs on the upper surface of the pile. The warmer the dung, the

faster the eggs hatch. The eggs hatched a couple of days later and

the larvae burrowed into the moist dung for food and warmth. It was a

half inch into one curd of the dung that larvae ate a bit of dung

that contained our Dorp.

Sam

asked, “What just ate us?”

“The

larvae of a Yellow Dung Fly,” Dorp answered. “They live in the

dung for about two weeks, where they will pupate

three times before becoming

adults, and will then crawl out of the dung to live out a six-week

life span.”

What

does ‘pupate’ mean, Mr. Dorp?”

“While

human children grow gradually; moment-by-moment and cell-by-cell,

winged insects grow by pupation. This means they grow a certain

amount in easily seen stages. Perhaps the most famous act of pupation

is when a caterpillar spins a cocoon around itself, then emerges as a

butterfly. Less attractive creatures, like dung flies

do the same.”

Sam

reflected for a moment then said, “That’s kind of a neat life;

like being born in a room full of pizza. Pupating three times in two

weeks and coming out as an adult. I wish I could grow up that fast.

Maybe they just grow fast to get out of the poop. Y’think?”

Time

went by, and their host larvae grew and pupated as it was supposed

to. Finally, came the day for the final pupation into an adult dung

fly. Dorp and Sam were in a cell just behind the left front leg. The

young yellow dung fly, a female, crawled out of the pile of dung to

begin her adult life. She shook her wings off, ready to fly. Suddenly

a field mouse came up and ate her. Dorp and Sam went into the stomach

of the mouse.

“Whoa!”

Sam yelled. “What happened? I didn’t know mice ate insects."

“Yes,

Sam, a lot of creatures

in the food web eat insects. You just learned

something new about the food web, eh?”

“I

guess so. What’s next? Are we going to be eaten by a fox, an owl,

or what?”

“Very

few mice die of old age,” said Dorp. “An attack by either of

those predators is possible, along with snakes and cats. Housecats

kill an estimated 2 billion small birds and animals per year,

including wild songs birds. But field mice reproduce quickly and

provide a lot of food for the food web. Field mice are the main

ingredient on many predators’ menu. I’m hoping it will be eaten

by an owl so you can see what it is like to be in an egg.”

Dorp

and Sam made their way through the mouse’s digestive tract and

found themselves as moisture in the mouse’s fur.

“So

howw do you laike my neww fou coat, dahlink?” asked Sam, as he

imitated a Hungarian actress in an old movie he once watched with

his grandmother.

”It

doesn’t match your shoes at all.” said Dorp dryly.

Suddenly,

they heard a flurry of wings and felt themselves rising rapidly, like

on a carnival ride.

Dorp

said, “Here were go. The mouse has been eaten by some type of bird.

Hmm, the flight pattern indeed feels like that of an owl. Let’s see

what happens.”

Sam

cut in, “You know how it feels to fly in an owl? Wow! We were in a

horse, in a Yellow Dung Fly, now inside the mouse, inside an owl. I

feel a blues song comin’ on.”

“Oh Sam. You don’t write music. Besides, if you were

going to write something out here, it should be a western ballad.”

“Mr. Dorp, right

now, ain’t no horse my friend. Besides, I got the gut-level blues,

three layers deep. Listen:

“I

know how Jonah felt, in the belly of that whale

I said I know

how Jonah felt, in the belly of that big whale

And just like my man Jonah, that belly has a tale.”

And just like my man Jonah, that belly has a tale.”

“I’ve

seen the inside of more critters, than anyone I know

I said I’ve seen the inside of more critters, than most anyone I know

I wonder if this is my payback, for shinin' so many bones, yea.”

I said I’ve seen the inside of more critters, than most anyone I know

I wonder if this is my payback, for shinin' so many bones, yea.”

“Most

every day, I spend time inside

a critter big enough to eat me, even one that I could ride

I’m so tired of being eaten, It really gets under my hide.”

a critter big enough to eat me, even one that I could ride

I’m so tired of being eaten, It really gets under my hide.”

"Gets

under my hide, get it? – ‘under my hide?’”

“I

get it Sam. Clever song. You may be able to cut an album by the time

you get home.”

"An album?" Sam asked.

As

the owl digested its meal, the mouse underwent several changes. In

the bird’s gizzard, the mouse’s fur and bones were separated from

its digestible parts. Those digestible parts continued through the

owl, while the leftovers stayed up above and were compacted into an

elliptical object called an owl

pellet, which the owl

regurgitated a few hours after the meal.

This is not the kind of

vomiting that humans do when they have the flu. The owl’s upper

digestive tract acts as a two-way street to intake food like mice,

and then, to expel the indigestible parts of the creature. Sam and

Dorp left the owl through the same orifice they entered.

The

owl pellet landed on the ground and when they evaporated out of the

pellet, they were caught up by a breeze and moved toward the east

across Nevada.

Photo: rickgorehorsemanship.com

Photo: rickgorehorsemanship.com

dorpwet.com

CHAPTER 2

Owl pellet.

photo: Science World